Kadaveri's 1980's Joshi Set Vol. 1

A look back on some of the most influential wrestling to ever graze our screens

Welcome, sickos, to what I hope will be an ongoing series of write-ups about my thoughts and impressions on the 1980s All Japan Women’s Pro-Wrestling! While I’ve at least dipped my toes into the 90s Joshi wrestling scene, going into this, the extent of my knowledge of 80s Joshi wrestling was limited to “I know the Crush Gals were a huge deal.” So when Twitter user Kadaveri started uploading the first of a multi-part, 70-hour-long compilation of the most important matches and moments from the decade to make it easier to get into this period of wrestling, I jumped at my chance to learn more. And so, after having seen the nearly 4 hours of footage in the first part of this compilation twice, I am eager to share my thoughts on what was a mind-blowing first look at the world of 80’s AJW.

What is AJW?

Let’s start with a little history lesson to understand the context surrounding the promotion at the start of this watchthrough. Remember that I am no wrestling historian; this is all a cursory look at AJW’s past. All Japan Women’s Pro-Wrestling, or AJW, was a Joshi wrestling (Japanese women’s wrestling) promotion started in 1968 from the ruins of the All Japan Women’s Pro-Wrestling Association, a coalition of wrestling promotions meant to capitalize on Mildred Burke’s tour of Japan with her World Women’s Wrestling Association (WWWA).

After a brief revival in 1967, the association gave way to AJW, with which most people are familiar. The promotion brought over Burke’s WWWA World Singles Championship and WWWA World Tag Team Championship to be the top titles for the promotion. Until the mid-70s, AJW followed a traditional booking strategy: Japanese face loses the top belt to a foreign heel, then promptly wins it back, rinse and repeat. It was not until the stardom of musical artist turned wrestler Mach Fuminake that the promotion shifted gears to focus almost exclusively on local talent for their main event scene. And no local wrestlers would make a more significant impact than the Beauty Pair.

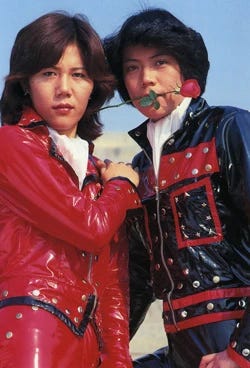

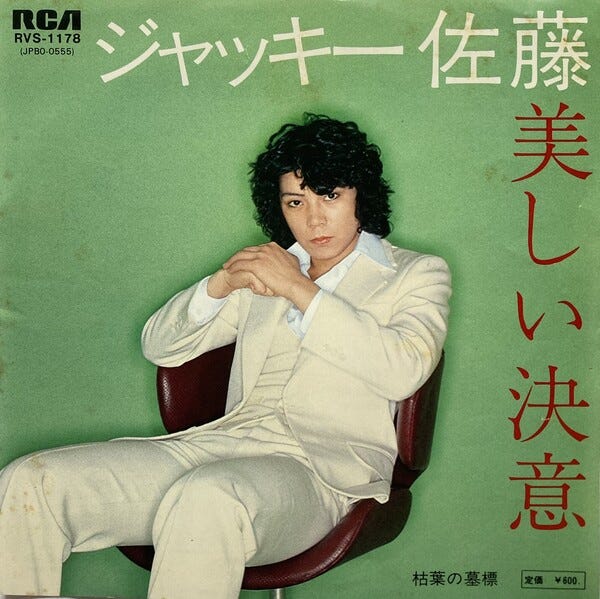

Jackie Sato and Maki Ueda formed Beauty Pair in 1976, blending pro-wrestling with idol pop music in a combination that would bring AJW unprecedented success in women’s wrestling and pro-wrestling as a whole. Beauty Pair drew thousands of fans to AJW’s shows, most of them teenage girls who idolized the pair and saw themselves in the duo. This would favor AJW in bolstering their roster, as thousands of young women would apply to become wrestlers at the promotion, inspired by Beauty Pair. Between wrestling, music, and even movie stardom, Sato and Ueda established AJW as a force to be reckoned with, but their time together at the top wouldn’t last.

AJW had a “Must retire at 26” rule for all of its wrestlers, a mixture of Japan’s belief that women should get married and start a family by that age and a desire from AJW to have their wrestlers be people young girls could see themselves in. One would question a rule that might handicap the promotion by cutting off the legs of popular acts, as it did Beauty Pair when Maki Ueda retired in 1979. Still, the promotion kept finding gold in younger generations, as we’ll soon get to both here and in future installments. This is where AJW finds itself at the beginning of 1980, with Jackie Sato, the remaining active member of Beauty Pair and WWWA champion and custodian of the immediate future of promoting a young Rimi Yokota.

Overall Impressions

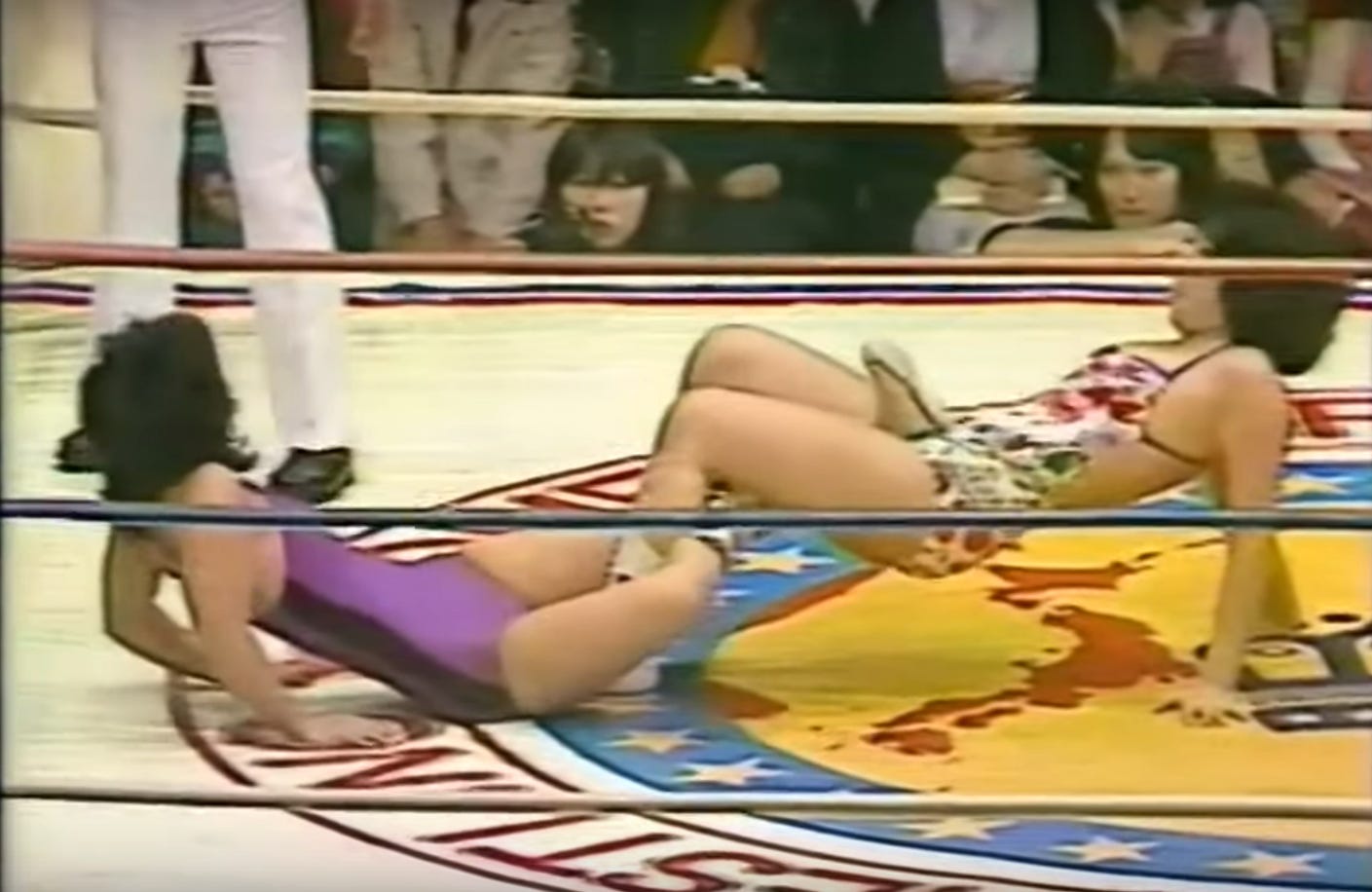

Now that our AJW primer is out of the way let's get to my thoughts on this first installment of the 1980s Joshi Set: holy shit! That exclamation sums it up: the matches shown here were intense, innovative, and captivating. It’s often said in hardcore wrestling circles that when you see an extraordinary move 90% of the time, it was invented by a Japanese woman 30-40 years ago, and the more I watch older Joshi matches, the more true that statement rings. It didn’t take long for this to take effect when, in the opening contest of Chino Sato vs Rimi Yokota, Sato pulled off a giant swing, a move symbolic of modern wrestlers like Miu Watanabe and Claudio Castagnoli. Slingblades, head scissors, reverse tombstone spots, it's incredible to see how these women pushed the art form forward, especially as other parts of the world were so slow in giving women’s wrestling the space it needed to grow.

I was struck by how urgently everything was executed in the ring. Often, matches will start at a blinding pace, with both opponents rushing at each other from the opening bell, rather than the two-count kick outs I’m used to. Pin attempts in AJW rarely last even for one count, as wrestlers will either bridge out of pins as soon as they happen or flip onto their stomachs before the pin can even be applied. When a submission hold is applied near the ropes, the wrestlers drag themselves to them instead of flailing about reaching for them. Things like these make the matches frantic, adding to the feeling of two athletes giving their all to win a contest.

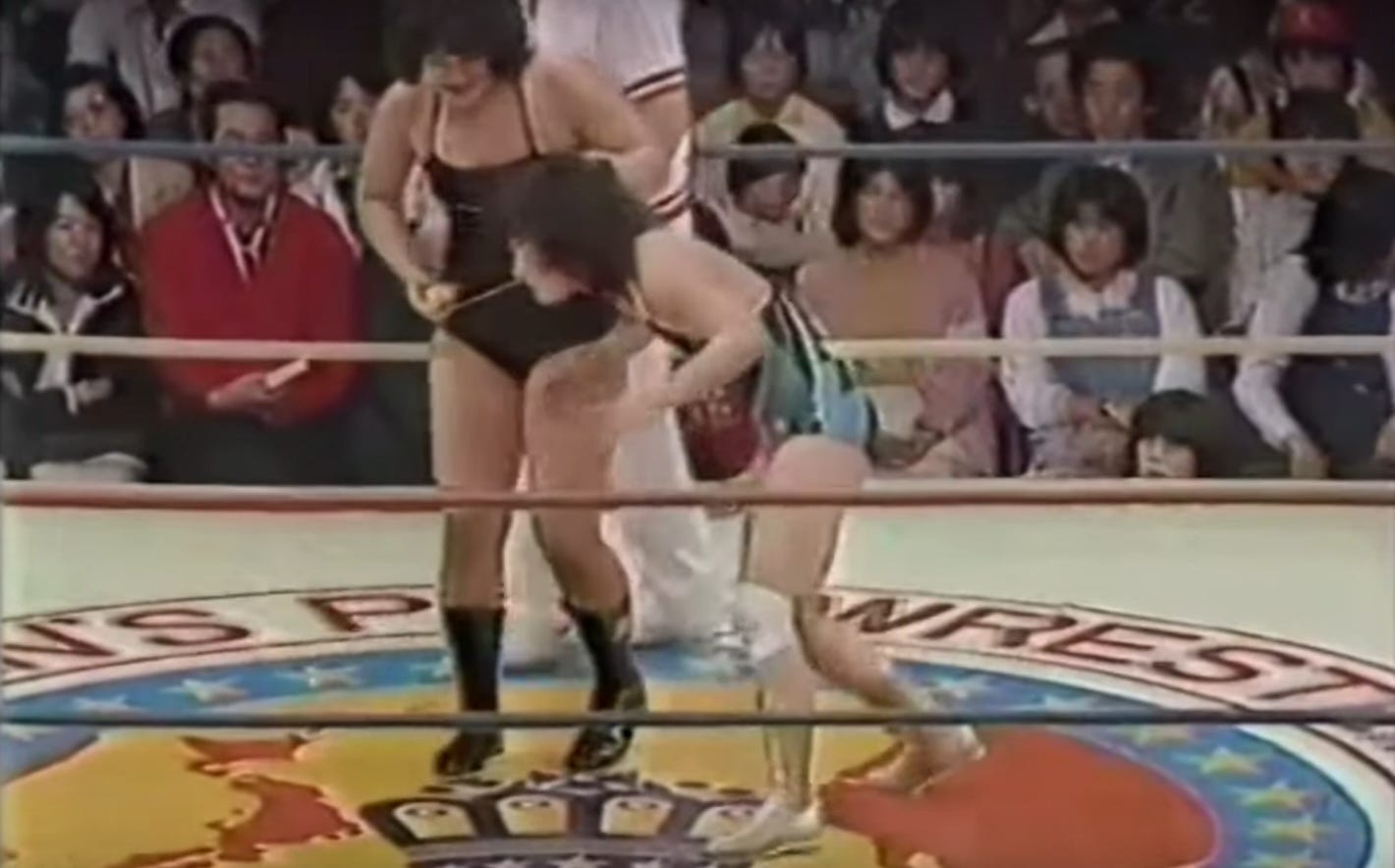

Fancy moves and fast-paced action doesn’t tell the whole story. Professional wrestling is an inherently violent art form, and there is no shortage of violence in 80’s Joshi wrestling. Stiff strikes and rough landings from high-angle suplexes are part and parcel of these matches, and the women of AJW constantly throw their bodies at each other to inflict damage. Weapons see regular use as well, with chair shots and announce table bumps occurring when the action spills to the outside. In particularly heated matches, the weapon use became more unorthodox, with cables being used to choke opponents or even a lemon being squeezed into the eyes of another wrestler to blind them. Despite the language barrier preventing me from fully grasping the context provided by the announce team, just from how a match would ratchet up the intensity, I could feel how much animosity wrestlers had for each other.

Nothing is perfect, however, and for as much fun as watching these matches was, I still have my nitpicks. Draws in wrestling provide exciting ways to advance feuds without necessarily placing either wrestler ahead of the other. However, too often, it can be a crutch bookers lean on to provide a high-stakes match without anyone having to take a loss. Of the 11 matches I watched, four ended in a draw, and it got to the point where instead of leaving me hungry for more, it made me say, “Really? Another draw?”. Referee obliviousness is a common trope in wrestling, but some matches here took it to the extreme. All too often, a heel brandishes a weapon in clear view of the official and hits their opponent with it, the referee seemingly more worried about trying, and often failing, to obtain the offending object than to admonish or disqualify the cheater. On at least one occasion, the time limit draw was used satisfyingly, but the incompetent officiating sometimes led to matches getting in their own way.

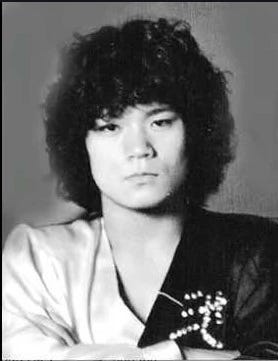

Jackie Sato

Effortlessly cool and incredibly skilled, it’s no wonder the young audience of AJW latched onto Jackie Sato as much as they did. The other matches in this first part of the collection draw great reactions, but Sato’s are on another level, exemplified best by her bout against Tomi Aoyama. From the start of the match, the crowd is electric for Sato, cheering on every move she lands on Aoyama and crying out in anguish when Tomi gains the advantage over her. Both competitors put on a hell of a performance in this match and had the crowd eating out of the palms of their hands for every near-fall, every dive, and every rough landing. A spectacular match that, if you’re not going to watch the whole collection, should be one of the highlights you do.

Sato is quite technically proficient, executing painful-looking submission holds and deadly slingblades alike. Everything she does is incredibly crisp and makes any opponent she’s up against look like a hundred million yen, not that she’s up against any slouches in the ring here. Sato puts everything into her performances as any promotional ace ought to do, and it shows its results in how the crowds take to her and how much success she brings the promotion.

Jackie starts off the 80’s Joshi set as the reigning WWWA champion, leading the company using her skills and popularity. Still, it is her relationship with the AJW Junior Champion that benefits from her status the most. The champion is a young Rimi Yokota, more famously known for her future name of Jaguar Yokota, and she is currently a protege of Sato. Before one of Yokota’s title defenses, she can be seen warming up under Sato’s tutelage as an interviewer gathers their thoughts about the upcoming match. I feel this relationship encapsulates my feelings toward Jackie Sato the best: a skilled star taking the promotion and its talent under her wing as it gets ready to progress beyond her, as Sato’s own forcible retirement from AJW comes the following year.

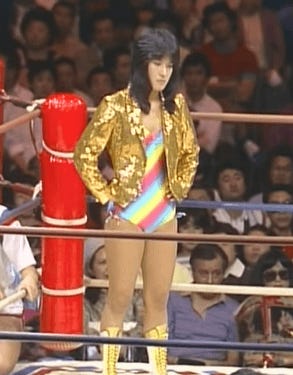

Rimi/Jaguar Yokota

If Jackie Sato is AJW’s present, then Rimi Yokota is poised to be the promotion’s future. Yokota was one of the many young girls who, inspired by Beauty Pair, would audition with AJW to follow in their idol’s footsteps. Despite not coming from an athletic background, she would take to wrestling like a fish to water and quickly rise the promotion’s ranks and win the AJW Junior Championship at the age of 20, within three years of her debut. If that wasn’t enough proof of AJW’s faith in Yokota, her being paired up with Jackie Sato as her on-screen apprentice is. The promotion saw a perfect passing of the torch moment between Sato and Yokota to lead AJW as their big star in the early 80’s.

Much like Sato, Yokota impressed me with her in-ring skills. While at a different level of proficiency than her teacher, Yokota shows why the promotion has so much faith in her. Her striking is stiff, and she isn’t afraid to get thrown around, especially during her match against Tenjin Masami. Her double underhook suplex, in particular, is a thing of beauty that I couldn’t get enough of in her matches. Rimi Yokota’s career will soon reach her idols' accolades, and I’m very much looking forward to the transition from a promising rookie to AJW Ace Jaguar Yokota unfolding.

The Black Devils

Every hero needs a villain, and the Black Devils are here to deliver in spades. Originally called the Black Pair, Yumi Ikeshita and Shinobu Aso served as antagonists to the Beauty Pair’s protagonists. After the retirement of Aso, Ikeshita would begin teaming with Mami Kumano under the same tag team name, and the two would continue to make their fellow competitor’s lives as difficult as possible. They liberally introduced weapons into matches, brought the match to brawls on the outside, kicked people while they were down, and avoided consequences as best they could. On multiple occasions, I cursed Ikeshita and Kumano’s names as they unfairly stacked the deck against the faces, wanting nothing more than for them to face their comeuppance.

The major highlight with this duo in the first part of the set was their 2 out of 3 falls match against the team of Tomi Aoyama and Lucy Kayama, the Queen Angels. From the get-go, the animosity between these teams is palpable, and they’re at each other’s throats as soon as the bell rings. It doesn’t take long for the match to break down as Balck Pair takes things outside the ring. Choking opponents with cables, slamming their heads onto announce desks, dives onto each other, both teams are eager to inflict violence on one another. The best example of Black Pair’s villainy is when, in between falls, Queen Angels’s seconds at ringside attend to Aoyama’s potentially injured knee, Ikeshita and Kumano lay their boots onto everyone trying to help. Many such moments make Black Pair easy to root against and get behind the heroes they oppose.

All this talk of Black Pair, but I didn’t title this section Black Devils for no reason. Ikeshita and Kumano would take a page out of Jackie Sato’s book and take on a protege of their own: Tenjin Masami, better known by her eventual title of Devil Masami. Masami is a powerhouse of a wrestler, quickly tossing her opponents around like it’s nothing and inflicting punishment as if it were second nature to her. If AJW is building up Rimi Yokota to be the next face of the promotion, it’s Masami they’re building up as the next major threat. In their match against each other in this first part, they are evenly matched, and Masami even gets the better of Yokota’s teacher, Jackie, by injuring her during a match. If there are two wrestlers to watch in the coming installments, it’s Masami and Yokota.

Closing Remarks

I must take this moment to once again thank Kadaveri for putting this compilation together for us to enjoy, as I can’t imagine it’s been an easy undertaking. To my knowledge, none of the matches presented in Volume 1 are on Cagematch’s database, meaning that without intimate familiarity with the period, tracking all of this footage would be incredibly difficult. Going to such lengths to preserve and share these essential moments in wrestling history for the enjoyment of fans all over is something that should be celebrated. I’m eagerly looking forward to future installments of the 1980s Joshi Set, both experiencing these pivotal moments in wrestling history and sharing my thoughts and feelings about what can only be described as Real. Joshi. Graps.